Climate Change in Urban Environments

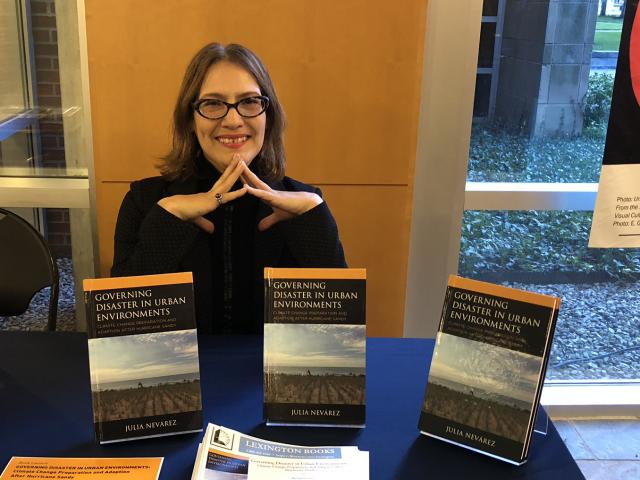

Julia Nevárez, Ph.D., Kean University assistant professor and sociology program coordinator, is the author of a new book, Governing Disaster in Urban Environments: Climate Change Preparation and Adaption After Hurricane Sandy. The book is available in e-book format at Kean’s Nancy Thompson Learning Commons.

University Relations interviewed Nevárez about the book that looks beyond efforts to rebuild infrastructure, and explores ways to rebuild communities.

How did you come to write this book?

My Ph.D. is in environmental psychology, so I have been dealing with environmental issues for a long period of time. I am originally from Puerto Rico, and I never experienced a hurricane. Then while living in New York, I saw the horrific images from Superstorm Sandy on TV. A week after Sandy, I volunteered in the Rockaways in New York. I was surprised at how community organizations developed relief hubs that functioned better than what I saw the government doing. These relief hubs provided people who lost everything with many of the things that they needed. There would be a truck with free food for everybody. Then there would be a tent with clothes for everybody. It was like a magnet for aid. I felt that the level of complexity for dealing with extreme climate while living in a city requires an interdisciplinary approach.

What is the book’s message?

In our approach to climate change, I think an important component that remains to be addressed is developing communities of solidarity to help locate and deliver needed resources for recovery, including food, water, cleaning materials and information to help communities prepare. The next steps in governing disaster in urban environments will be to become active citizens, who strengthen social ties and work toward the common good by finding and sharing information and developing strategies, in meetings and conversations with others, to prepare for extreme climate impacts.

What role do cities play in climate change?

There is this notion of the “Anthropocene Epoch,” which unofficially redefines the human impact on Earth as a geological period. In that regard, the role of the city is a paradox because the city becomes the root of that problem — the problem of industrialization, the problem of pollution, the problem of carbon footprint — but it’s also the solution because most progressive initiatives about climate happen in cities.

You write about resiliency in the book. How do you define it in the context of extreme weather?

Extreme climate hits people who lack resources, or poor people, harder. After Sandy, resiliency became the buzzword. It implies the capacity or ability to bounce back after a challenging event. When we are talking about recovery after an extreme weather event, it is usually a priority to think about rebuilding physical infrastructure. Boardwalks were erased on the coast in New York City and New Jersey. Houses were flooded. But one of the most overlooked aspects is social resilience. I look at the whole community and take the situational awareness approach, a way of looking at communities and working with them to fill in the gaps of what the government can and cannot do in specific communities.

How does the conversation need to change so that social infrastructure gets the attention it deserves?

After Katrina, after Sandy, and more recently after Maria, civic engagement increased dramatically, so I think that these communities of solidarity kind of emerge from these very dire situations. At the end of the day, what we need are more spaces, physical spaces and online spaces, in which we can have conversations about this and many of the challenging issues we are facing.

I tell my students to develop a curiosity and continue exploring and seeking alternatives, to take a research approach in everything that they do. If we do that, that will help move the conversation forward.

I also believe that we should call the threat “extreme weather impacts” rather than climate change. We understand the challenges of climate change, but it is hard to make the connection between that and everyday life.

Where do we go from here, in cities and elsewhere?

We develop communities of solidarity by creating relief hubs where many different community organizations can work together, and for the government to work in unison with those communities. This is a ground-up model, rather than top-down, which tends to be very bureaucratic and highly inefficient.

There are specific actions that can be implemented immediately, such as working groups to develop 72-hour plans, scenario planning to prepare for extreme weather events, and mapping out vulnerable areas in the communities.

This is a pressing issue because it is very likely that we will see more of these challenges, and we are not equipped to deal with them economically, psychologically and socially.